Hijabed or not Hijabed, To Each Her Own

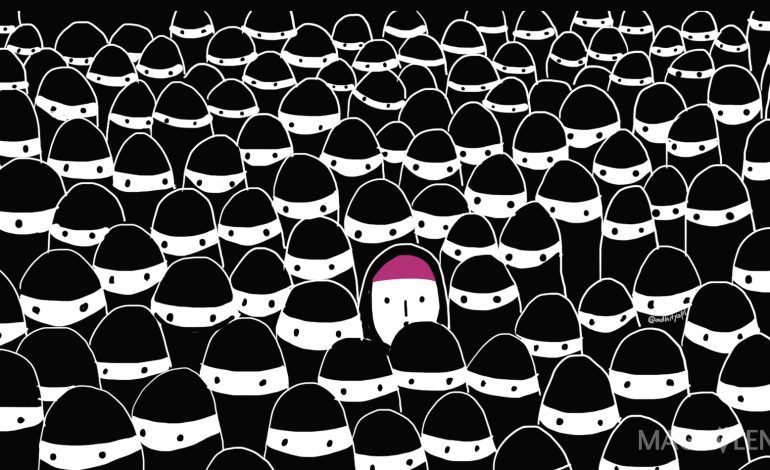

The number of women wearing jilbab and the pressure to wear longer veil that covers the whole body reflects a misunderstanding of the Islamic teaching on hijab.

Women’s rights activist Hasmida Karim handed me her cell phone during an international seminar at the recent Women Ulema Congress in Cirebon, West Java.

“Please, take my picture with Hatoon,” she said, referring to Hatoon Ajwad al-Fassi, a women’s rights activist and an associate professor of women’s history at King Saud University in Saudi Arabia who was one of the speakers at the Congress.

“I want to show my friends who wear the so-called shar’i hijab down to their legs that even Saudi ulema wears a simple veil,” said Hasmida, who comes from Kendari, Southeast Sulawesi.

Parallel with the increasing religious conservatism in Indonesia is the proliferation of women who wear hijab, which is considered an obligation by mainstream Indonesian Muslims despite dissenting opinions over it among Islamic schools of thought. The more conservative society becomes, the longer grows the length of hijab sported by Indonesian Muslim women. From covering the chest, once seen as the more modest of the jilbab, some hijab has grown to thigh-long, and some as far down as the ankle.

Hasmida and several friends of mine who wear short hijab said they are often scolded by those wearing the “shar’i hijab” for not being Islamic enough. The shar’i-wearing hijab women even held a campaign once at the Hotel Indonesia roundabout in Central Jakarta, holding posters and banners to show “the right way” of wearing hijab.

So, amid this phenomenon and the rather similar hijab style at the Congress, it was indeed refreshing to see the various styles of head covers worn by international participants and speakers during the Ulema Congress. Pakistani ulema Bushra Qadeem Hyder, for example, wore a long scarf that still slightly reveals her neck and hair, the same style as Nobel Peace Prize winner Malala Yousafzai. So did Roya Rahmani, the Ambassador of Afghanistan for Indonesia, who looked chic in a high bun under her see-through scarf. Malaysian Zainah Anwar, the director of Musawah, a global movement for equality and justice in the Muslim family, did not even have her head covered.

The most unexpected, however, was Hatoon Ajwad al-Fassi, who wore a long sleeve and high collared bohemian shirt with a long skirt, and a head cover similar to that of a Catholic nun. She could not be further away from the stereotypical image of Saudi women with long, black abaya and niqab, the kind religious fundamentalists here in the country emulate.

The most unexpected, however, was Hatoon Ajwad al-Fassi, who wore a long sleeve and high collared bohemian shirt with a long skirt, and a head cover similar to that of a Catholic nun. She could not be further away from the stereotypical image of Saudi women with long, black abaya and niqab, the kind religious fundamentalists here in the country emulate.

The clothes that she wore, Al-Fassi said, is the traditional outfit from her home region in central Arabia, which she has worn since she was a student.

“Saudi Arabia is multicultural, similar to Indonesia. What people see from outside is one culture, which is a problem within Saudi Arabia, because the culture of the rulership, the Central of Arabia, is forcing itself on the rest of the country,” she said.

“People are commenting all the time; calling me racist because they say I promote this (culture). I have worn my costume for over 35 years on a daily basis to show that we have different cultures, rather than wearing all black. Recently, even men have started to look into their heritage. More and more men wear traditional turbans. There is a revival of multiculturalism. In the south, women wear colorful hats, big hats like Mexican hats because they work in the farm and they don’t cover their face.”

Uniformity

Prior to the Women Ulema Congress, in a chat group set up for the all participants, the committee had warned the participants, “Since the Congress is held inside an Islamic boarding school complex, please be mindful of what you wear. Let’s remind each other.”

Hasmida told me later that there was a rumor circulating among participants, warning them that a group of feminists were going to “infiltrate” the Congress. This took me aback. Do these people think we cannot dress appropriately? Do they think we would just go Femen on them?

In the end, the feared infiltration by indecently dressed feminist never happened. Everyone dressed appropriately. But during the three days I attended the Congress in the hot and humid coastal city, drenched in sweat in sessions held outdoor or inside non air-conditioned rooms, I could not agree more with the opinion that (the teaching on) hijab must be understood contextually (of course, the other side would give that tired argument that “hell is hotter”).

“One of the most important versions in fiqh is the ethics of dissenting opinion…If Muslim society wants to return to the golden age of Islam, the key is differences in opinion,” said Lailatul.

I respect a woman’s choice to wear hijab, but I am very much against the growing attack and hatred against those who do not wear it, and the hell that breaks loose if a woman decides to remove her head cover. Ulemas or Muslim scholars with extensive religious academic credential who are of the opinion that hijab is not obligatory are quickly labeled heretic by people whose religious knowledge is shallow and superficial. Their daughters, who have the free will to not wear hijab, get bullied on a daily basis. Common people like us are mocked and scolded at religious gatherings (once I, and several other women, were shouted at by the imam during Eid prayer) and family meetings or even at workplaces for going veil-less. Numerous memes circulate against hijabless women, comparing them to a piece of uncovered meat swarmed by flies.

Nong Darol Mahmada, a women’s right activist and the co-founder of the Islamic Liberal Network, who wrote the introduction to the book Kritik atas Jilbab (the Criticism on Jilbab), said the situation has gotten out of hand and leading to the misunderstanding of the nature of hijab. The teaching of wearing hijab is also understood in the most literal way, instead of wearing decent and modest clothing.

“People are now quick to judge others based on what they wear. They even go as far as calling ulemas’ wives back in the 60s or 80s who were not wearing full hijab as not understanding Quran. That is so disrespectful,” she said.

Having grown up in an Islamic boarding school and graduated from an Islamic university, Nong said she is a staunch critic of jilbab and other religious practices that do not respect women’s authority over their body.

As far as her concern, she said, there was no verse in the Quran that obliges women to cover their hair.

Participants of Women Ulama Congress (KUPI) taking picture with speakers from other countries.

“In Surah Al-Ahzab and An-Nur, the most important point is covering the chest, not head. That’s because during the Jahiliyah period (the dark era before the Prophet Muhammad’s), women were not covering their chests. So, verses were written to respond to the condition or context of the situation,” Nong said during a discussion on “The Freedom to Wear Jilbab” held last week by Indonesia Feminis group.

“Verses about jilbab are also political and elitist. The verses were meant for the Prophet’s wives and children, to distinguish them from slaves, so they would not be disturbed. The situation is different now, women are not as objectified as they were. So for me, hijab is not obligatory. It’s not part of the five pillars of Islam. But if you’re comfortable wearing it, it’s your choice.”

Lailatul Fitriyah, a researcher and a PhD student in theology at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana, said hijab falls into the territory of fiqh or Islamic jurisprudence, which is very diverse in terms of point of view and very dynamic.

“One of the most important versions in fiqh is the ethics of dissenting opinion. This is what is missing now. Islamic jurisprudence is very diverse, but now it tends to be uniformed. If Muslim society wants to return to the golden age of Islam, the key is differences in opinion. Remember that Allah does not want something to be more difficult for the ummah (whole Islamic community),” said Lailatul, who is also known as Laily, during the same discussion at Kinosaurus, South Jakarta.

Self-enrichment

So, is hijab obligatory or not? Is it liberating or oppressing? The answer is both for both questions, Laily said.

“It depends on the context. I’m criticizing the International Hijab Day because it homogenizes Muslim women and it is insensitive for those who are oppressed. Why not just make it the International Muslim Women’s Day?” she said.

For her personally, jilbab has spiritual aspect, a symbol of her dedication to God, whether or not there is a verse about hijab.

“Hijab also has a social aspect for me. It is a reminder that I am a different individual in the community (where she currently lives in the US). Therefore, I have to protect those who are also different,” Laily said.

She also criticized feminists’ criticism over Islam that presume that everything was misogynistic back in the days of the Prophet.

“True, most space was filled by men, but it didn’t mean that there weren’t many voices by women. Agency is not homogenous. In Egypt, women wear niqab but that doesn’t automatically mean that they don’t have agency,” Laily said.

“Third-wave feminists are also of the opinion that the more we liberate body and sexuality, the freer we are. If we define freedom as open and sexual, it reduces freedom itself. So it’s just about breasts and vagina then?” she added.

She urged Muslims to stop seeing something as obligatory or non-obligatory and black and white.

“Islam is a civilization, a form of culture and a product of history. History does not work in a linear way. It has been changing and growing since the 7th Century when it was born,” she said.

“Religion is not about heaven or hell, but about how we enrich ourselves to become a better person. Being Muslim means being the most useful member of society.”

Read Hera’s piece on women’s role in radical religious groups and follow @heradiani on Twitter.

Check out this TedTalks about “What does the Quran really say about a Muslim woman’s hijab?” by Samina Ali