Women, Power and Politics of Earthsea, the Fantasy Series

A note on the 1960's fantasy series Earthsea and how such tales of dragons and evil spirits are really a deep reflection on politics, feminism and existentialism.

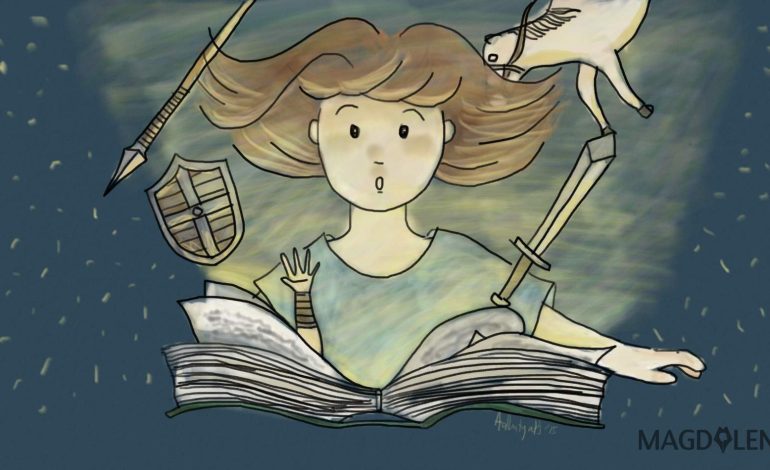

As a little girl, I often felt a bit different from the other kids. I would find my peace in the solitude between the pages of books, tales that would whisk me away from the constantly nagging world that I often felt misplaced in. The heroes of these stories, the underdogs and the alienated, they gave me comfort with their wonderful adventures and their magnificent worlds so different from ours.

One thing I only realized recently is there is not much place for a female heroine to thrive. Even in the world of fantasy where the authors ideally have the freedom to conjure up any sort of world they want, we don’t get to see many women having equal opportunity as men to create an impression on the readers. Women’s roles are often downgraded to mere damsels in distress, or the beautiful maiden whose hands the hero seeks, or at the most, a trusty sidekick.

Except in Earthsea, a fantasy series written by the award-winning author, Ursula K Le Guin. The stories are set in Earthsea, a world primarily consisted of islands and archipelago, not unlike Indonesia. The series offers a view to a very rich culture, balancing the beautiful diversity of the islands with the intricate storylines of the heroes to weave these wonderful tales.

On the second installment of the series, Le Guin takes us all the way to the far eastern part of the world, the Island of Atuan of the Kargad Lands. The Tomb of Atuan tells the story of its heroine Arha/Tenar. It is very refreshing to finally have a strong female character as a significant figure in a world that is mainly dominated by male heroes.

In the fantasy world, we’ve seen enough women preoccupied with domestic issues – those gentle women who take care of their children and keep the hearths warm. We’ve also seen plenty of women warrior, those who will not bow down to the traditional gender roles and prefer to take arms alongside their brothers to defend the realm. Tenar was neither of these. She was strong not in the brutal way of men; she was strong without having to deny her more feminine nature and The Tomb of Atuan beautifully crafted the story to illustrate her strength.

In the after words, Le Guin wrote “the women warriors of current fantasy epics – ruthless swordswomen with no domestic or sexual responsibility who gallop about slaughtering baddies – to me they look less like women than like boys in women’s bodies in men’s armor.”

I think this is what we’re majorly missing in modern fantasy stories. The ways of patriarchy have led us to think that for women to be regarded as being as strong as our male counterparts, we also have to have the brute strength of the battlefield warriors, and that we have to achieve whatever they have achieved. As much as I admire and adore these female warriors, we often forget that there are also strength in kindness and compassion, bravery in perseverance.

As much as I want to see our heroines rise up to a position as high as a king and the recognition of a valiant knight who has slain thousands in battles, we are faced with the reality, both in fantasy or real world, that these women are not in a circumstance where they are given the same opportunity as men. To impose such honor and impression from the readers on such female characters prove to be much trickier than we expect it to be.

Le Guin talked about two different meaning of power. There is “power to”: strength, gift, skill, art, the mastery of a craft, the authority of knowledge. Then there is also “power over”: rule, dominion, supremacy, might, mastery of slaves, authority over others. While Ged, the male protagonist, is offered both kinds of power, Tenar is offered only one.

With the hierarchy of society, the world of Earthsea is the world of power over, a world in which women have always been ranked low. A girl could be at the heart of the story, but she couldn’t be a hero in the hero-tale sense. As Le Guin put it, fantasy isn’t wishful thinking, but a way of reflecting on reality.

The ways of patriarchy have led us to think that for women to be regarded as being as strong as our male counterparts, we also have to have the brute strength of the battlefield warriors, and that we have to achieve whatever they have achieved.

Written back in 1969, that fact rang even truer now. So Tenar is given the power over. She is a priestess, the greatest of all priestesses, even the king himself bowed down to her. Yet, she is a slave to her own power, her being belongs to the people she serves. It isn’t until she meets Ged, who has been her prisoner by then, that she is able to exert her power to, her freedom of choice. By helping Ged, she is able to help herself.

When she faces her prisoner, she is faced with herself. She must question her faith, her purpose, everything she has learned and everything she knows. She is strong not because she can slay dragons or move a mountain with a flick of fingers, but she is strong because she is brave enough to question her own humanity. She is strong because she is brave enough to help a stranger for what she thinks is right and puts her faith and her life in the stranger. She is strong because she is brave enough to leave her life and everything she has known behind to face a strange new land, despite everything she has been taught to believe, because she feels in her heart that it is the right thing to do.

I wouldn’t say The Tomb of Atuan is a feminist story because that would undervalue the full scope of what the book manages to achieve. To me, this tale is a story of how a girl truly found herself, who she is as a person. This is a story about rebirth, finding faith and facing life. Underneath all the fantasy mumbo jumbo, Tomb of Atuan is a book with one of the truest insights of growing up and discovering yourself as a person.

To this day, I think the whole series of Earthsea is a very relevant story to read, even in this modern age. Cleverly crafted with a beautiful veil of magic and sorcerers, Earthsea is a tale to reflect on our own world. With a diverse cultural and racial characteristics, Earthsea is a refreshing take in the world of fantasy. It addresses the issues of power and politics, feminism and social hierarchies, faith and existentialism, and every aspect in life worth reflecting on.

It is a tale of dragons and evil spirits, but beyond that, it is also a story about humanity. Earthsea is an excellent series and it is something I would strongly recommend to anyone who is into good classic fantasy.

Prameswari Noor Andytaputri is a redhead and a pie enthusiast with a strong affinity for cats. She can often be found with her head deep within the pages of a book, but she wouldn’t mind putting the book down for an amicable discussion on mythologies, gender issues, or the latest episode of Game of Thrones.